By Ankita Shrestha, ICIMOD-HI-AWARE

It is not a new finding in good governance research that there should be discord between and discontent among citizens and government authorities, provided that the end goal of such research is to attempt at closing these fissures. Notwithstanding the waves of political uncertainty through which the country wades to this day, Nepal has yet to see government practices meeting the expectations of the local people for whom local government, particularly district authority, is sometimes non-existent.

In two situational analysis field visits made in Chitwan earlier this year, a similar situation was observed. Although efforts at the formal institutional level go largely unnoticed, owing much to the nature of such institutions whose inherent purpose is to carry out government roles outlined by prescribed policies, lessons learned in the field indicate a sharp dissonance in the efforts made at the government authority level and the satisfaction felt at the local community level.

The district headquarters of Bharatpur in Chitwan District lies 160 kilometres south-west of Kathmandu. The Narayani River flows southward into Bihar, India, through Chitwan, and is a major part of the natural and human environment of the district. The district headquarters is also home to major hospitals, educational institutions and government offices, including the District Development Office (DDO), which works on issues linked to providing irrigation and drinking water, preventing flood and erosion, protecting riverbanks, mitigating the effects of water-induced disasters, allocating resources and implementing development plans in Chitwan.

Confluence of the flood-prone Rapti and Narayani Rivers visible from Meghauli VDC.

Confluence of the flood-prone Rapti and Narayani Rivers visible from Meghauli VDC.

During the field studies, an overwhelming consensus that flooding is and has been the most prominent and recurrent issue in Chitwan was found between the district officials and the local communities. People in particular risk of flooding in the coastal areas of the Narayani River and its tributaries felt the worst impacts of water-induced hazards, including siltation, loss of soil fertility, loss of crop and reduced crop quality, livestock and habitat endangerment and loss of human lives.

Testimonials from residents living this reality painted a harsh picture of those communities located farthest from the district offices, namely the Chepangs and Dalits mostly living near the riverbanks, as they were left with minimal coping measures against the adverse impacts of floods on water, agriculture, health and tourism, and therefore livelihood.

It is hard to imagine that the people living in Chitwan’s flood-prone areas have experienced decades of neglect and abandonment by the government authorities. Flooding in this area seems to have become a recurrent problem since the late 1950s, when Chitwan, a largely uncultivated forest area, was deforested under the Rapti Valley Land Development Project—an effort to not only encourage settlement in the area but also eradicate malaria. Chitwan has since become prime farmland, and migration to the area from all over Nepal continues to this day.

The DDO officials in Chitwan echoed this disbelief, as every fiscal year, funds and resources were allocated to the Village Development Committees (VDCs) for the prevention of flood and erosion and to protect riverbanks. With the participation of the local people, the VDC personnel have constructed gabion walls in select VDCs generally located near the district headquarters and installed early warning systems in Deoghat, located on the outskirts of the district. The officials added that those VDCs located farther away from Bharatpur, separated from the rest of the district by the Royal Chitwan National Park, had been left conveniently bereft of most of these flood-management efforts, owing mostly to limited budgets and the VDCs’ historical geographical isolation.

Despite such efforts, the local government in Chitwan District can still seem detached from the realities and the embitterment of the local people who seem not to figure in the minds of the government authorities. Over the years, flooding has occurred every monsoon and has swept away the barriers, which were almost entirely destroyed soon after they were constructed. Locals complained that not only was flood-management work done without proper knowledge of the riverbanks, but the construction of barriers sometimes caused rivers to meander into different zones, causing new erosions.

Gender disaggregated Focus Group Discussion in Ayodyapuri VDC, where the early warning systems had been installed but were found ineffective.

Gender disaggregated Focus Group Discussion in Ayodyapuri VDC, where the early warning systems had been installed but were found ineffective.

Sirens had been installed in the municipality offices of some VDCs, and even in Ayodhyapuri, which is located farthest from the district headquarters. However, people did not find the early warning systems effective, especially during flash floods, when sounding the alarm—to alert the rest—meant risking one’s life to reach the municipality offices. Elsewhere, these warning systems had not seen the light of day. Even in Mangalpur, the VDC nearest the district headquarters, local people who had knowledge of the installation of early warning systems in Deoghat dismissed their usefulness, citing that these warning systems, mainly operated through sirens and mobile phone information transmission, existed in a parallel world of which they were not a part.

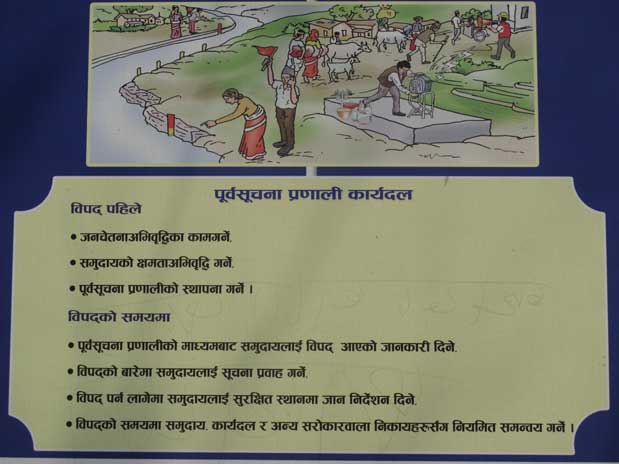

A roadside hoarding board installed by the Government of Nepal and the United Nations Development Programme displays information about the flood early warning systems, which can be made more effective.

A roadside hoarding board installed by the Government of Nepal and the United Nations Development Programme displays information about the flood early warning systems, which can be made more effective.

While some local people were critical of the government’s providing only little help in the name of disaster relief for flood victims, sanctioned as minor relief funds, others were hopeful about increased preventive efforts from the state in the years to come, in terms of resource allocation for riverbank reinforcements and better flood management. A larger group of people, however, were indifferent. When asked whether their local government officials had been made aware of their discontentment, their answer was almost unanimous. “We do not expect anything from the government”.

A local politician would help elucidate. This overwhelmingly common response had now become hegemonic concept, especially in those communities outside the margins of governmental jurisdiction in which people have not held and would not hold the government responsible for anything, and consequently, do not expect anything in return. Worse still, expectations, where present, were lost in mistrust of government officials, of which the officials were either unaware or dismissive.

While discord and discontent may overshadow the current flood-related governance scenario in Chitwan, government officials in the DDO are positive about the future, in which they anticipate plans and policies that prioritise local-level river-water management and disaster-mitigation measures. Whether these projections play out as awaited currently depends on various political upshots, but putting emphasis on and bringing more attention to water governance, or the lack thereof, both at the local and authority level, is the crucial step towards which research must be led.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author, and should not be attributed to the organisation or project she is affiliated with.